Robert Noble was the quintessential ANZAC soldier- a young man with no military experience leaving Australia’s shores. He never returned.

Introduction

The First Australian Imperial Force was perhaps the most significant recruitment of troops for the Australian war effort for the Great War. Around twenty thousand men enlisted to be trained overseas and sent into battle, from all regions of Australia, including Canterbury. A number of these men would go on to be part of the ANZACS in the Gallipoli campaign.

As the first large scale war of its kind, World War I presented a formidable logistical challenge. An often overlooked element of this operation was the transmission of letters and missives, and in particular, the transport of soldier’s effects after their death. Often these possessions and communications went missing, leaving families in Australia unsure of what happened to their loved ones.

The Noble Collection comprises a unique set of objects dating to the First World War and the Australian Imperial Force. Robert Henry Noble, the younger son of a Belmore resident, died in 1916 on the western front, and is the central focus of these objects.

From war medals in their original packaging to a hand written letter from an anonymous fellow soldier, The Noble Collection paints a picture a family left behind desperately searching for news of their beloved son, and at its heart, something to hold onto.

Who Was Robert Noble?

On the 22nd of May 1916 at 2.30 pm, Robert Henry Noble enlisted in the 36th Battalion of Australian Imperial Service at 24 years of age. The clear, elegantly sloping lines of his signature on the attestation paper bespeak his previous work in administration; Robert spent his short adult life before the war as a bank clerk. He is described in his service record and a Red Cross report as fair, tall and blue eyed. Like many of the young recruits that never came back from the Great War, we know little of his childhood. His father, Thomas Noble, was a resident of Belmore. We also know from the reverse of his watch that he spent time at a Sunday school in Newtown in his late teens. Born in 1892, Robert grew up in a progressive time in Sydney’s Inner West; electricity and rail opened up the area stretching back to Canterbury for new residential development. This area was a curious haphazard arrangement of large scale industry such as brick-making and manufacturing alongside pleasant federation housing, with access to the city like never before.

The Australian Imperial Force had only been sent to the Western Front for three months before Robert Noble enlisted. After a year of training in England, he was dispatched to Rouelles in June 1917. Only four months later on the 12th of October, he was reported missing in action and later confirmed as deceased in Belgium. He had been fighting as reinforcements for the 8th battalion.

According to a Red Cross report, Robert died from a shell at Passchendaele in the third battle of Ypres. The conditions at Passchendaele were severe, with heavy rains reducing the trenches to mud, resulting in high deaths for the Allies. It was these attacks in which Robert died, and over 38,000 others, that convinced the Allies to withdraw; a lengthy process that stretched into November 1917,

These charming postcards show Robert Noble as civilian and soldier. At the top right is a photograph of Robert dated to 1913, two years before his entrance into the AIF. He wears a three piece suit with a tie and a cleanshaven visage typical of the era. His transformation from the reserved civilian to soldier is directly apparent in the three other photographs. Here Robert is depicted in full AIF uniform. These postcards represent the cheerful, enthusiastic touch that inhabited the minds of Australians and others before the realities of war had come fully to be understood.

Bad News

It is difficult perhaps to imagine what a life in WWI Australia was like for friends and family waiting for news of their loved ones. Death tolls for the First World War for Australians were in excess of sixty thousand. Mothers and fathers, sons and daughters, partners and sweethearts all had a vested interest in Allied Victory and an end to the Great War.

Those in Australia received news in various ways of military exploits abroad. At its most general, the media covered the war and provided general movements entwined at times with patriotic fervor, morale boosting undertones and, as the war progressed, increasing dismay at loss of life. The Red Cross spent considerable time and resources in investigating wounded and dead soldiers, relaying information back to the Australian Infantry Force and next of kin. But the most immediate and frequent messages came from letters written by soldiers themselves, written in the conditions of war and hopefully transmitted back to their homelands.

Robert’s father, Thomas, received a report in 1917 that Robert was classified as missing following the Battle of ~~. A letter from Robert’s sweetheart, Rita Hamlyn, addressed to the AIF tells us that the Red Cross in Sydney were investigating the circumstances of his disappearance. Rita was aware that some soldiers of Robert’s battalion, the 36th, had been taken prisoner. Unbeknownst to her, Robert, unfortunately, was not one of them.

The Red Cross letter shown right represents the first official confirmation the Noble Family received of Robert’s death. The Wounded and Missing Enquiry Bureau Files held at the Australian War Memorial indicate the tireless work of the Red Cross; interviews with fellow soldiers, cross-referencing with lists and double checking of records to ensure that the information is accurate. Enclosed in those files are also thank you notes from fellow soldiers who enquired after Robert’s status and sent word home to his family. It is likely the Noble family knew of Robert’s death before the official missive came to them.

Something To Hold Onto

Following the news of Robert’s death in 1918, the family then waited on the return of his effects and the transference of his will. The wait was a long one; the National Archives of Australia have a letter sent by Robert’s brother to Base Records asking for some news of Robert’s things, as other families in the area had received theirs some time ago. The lieutenant who found Robert’s body had written back to the family to say he had secured Robert’s things and had given them to the battalion commander. Despite the delay, Robert’s possessions were indeed on the way. There were two cases shipped out from London on the ship “Barunga” containing wallets, a notebook, photos, postcards, a fountain pen, protractor, school of instruction certificate, spectacles, razors and a bible in November 1918. A letter from Base Records promptly followed to confirm the packages.

And yet, a year later and the objects had not arrived. Again Robert’s brother wrote to Base Records, stressing the importance of receiving Robert’s things, particularly for his father who wanted something of his beloved son to remember him by. In July 1919 came the terrible news that the S.S. Barunga had been lost at sea due to enemy action, the letter stating “No hope can be entertained of the recovery of these articles”. It seemed then, that his father’s wish to have some small memento of Robert’s “going west” had come to an end.

In a surprising turn of events, a package arrived in late 1919 to Reiby Sunday School, Newtown. This was Robert’s old Sunday School from childhood where he had spent years playing (cricker) with other local boys. Enclosed in rough, brown paper was a letter from a former private. Mr J.H. Page had been part of the exhumation crew that came upon Robert Noble’s body and noticing a watch on his left wrist, removed it in order to send it to the family. As he writes, “I have had this in my possession over 12 months now + wondering whether to send it to you or not, as naturally a small thing as this even brings back sorrow and grief.” He couldn’t have made a better decision. Encased in cardboard and cotton wool was Robert’s watch given to him by the Sunday school, the watch that had accompanied him to the Western Front. Finally, Robert’s family had something of their son that had returned from the trials of war.

Medals

Mr Page’s letter and the accompanying watch must have seemed a miraculous gift for Robert’s grieving family. Finally in possession of something of their son and his ‘trip west’, the next few years saw a stream of keepsakes and awards recognising Robert’s service. When these items were donated to the library in 2010, their historical value was instantly apparent. They were wrapped and packaged in their original boxes and envelopes.

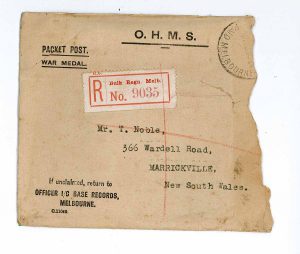

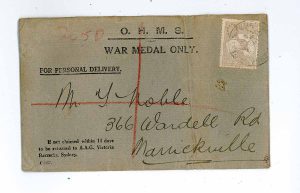

Robert Noble was awarded two medals posthumously for his service on the Western Front. The first, pictured left, is the British War Medal. The British War Medal was approved in 1919, recognising and commemorating the service of those who campaigned between the 5th of August 1914 to the 11th of November 1918. The obverse, shown here, has the head of George V with his titles. The reverse shows St.George on horseback trampling the eagle shield and skull and cross bones, symbols of the Central Powers. The sun of Victory shines in the background.

Pictured alongside is the original envelope addressed to Robert’s father at their residence at Marrickville.

Robert also received the Victory Medal posthumously. This was also authorised in 1919 and given to soldiers who served in the Great War between August 1914 and November 1918. Made of copper with bronze lacquer, the medal depicts winged victory on the obverse, and the reverse has a laurel wreath with the words “THE GREAT WAR FOR CIVILISATION 19-14-1919”. A rainbow ribbon is included.

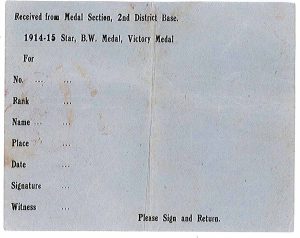

This Victory Medal has all of its additional ephemera and has never been threaded. The rainbow ribbon and medal are enclosed in a small envelope with flap. These go into a small labeled box (not pictured) with a receipt slip which would have been sent to Victoria Barracks to confirm the medal’s arrival. Photographed also is the original envelope addressed to Robert’s father.

Memorial Scroll and Plaque and King’s Address

The loss of life that resulted from the Great War had a significant impact on communities everywhere. Canterbury was no exception. There was a driving need to remember the fallen, encapsulated in the phrase “Lest We Forget”. Like many other Australian communities, Canterbury erected a number of memorials in common spaces. This included the clock tower at Anzac Parade and the delicate marble pillar at Hurlstone Park, almost like a chess piece, sheltered by leafy trees. Honour Rolls, detailing the dead from each local government area, were placed in newly forming Returned Soldiers League (RSL) clubs, also known as ex-servicemen’s clubs.

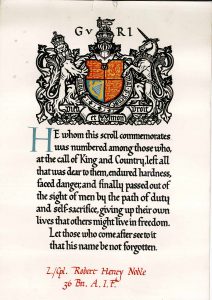

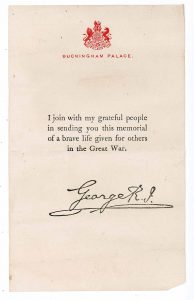

Following the authorisation and transmission of medals to soldiers, the British Government devised the idea of a memorial scroll which could be sent to next of kin of fallen soldiers in recognition of their service. Sent out in 1922 in round cardboard cylinders, the Memorial Scroll is delicately and gloriously designed with the Royal Crest at the head.

As early as 1917, the UK government sought to create memorial objects for fallen soldiers, appealing to the public for designed in a nationwide competition. This resulted in the memorial plaque, a weighty bronze circle emblazoned with Britannia and the British Lion. In the photograph, Britannia bestows a laurel crown upon the name of ‘Robert Henry Noble’. Each soldier had their name individually marked out on their respective plaques. This is a later example that bears the makers mark of Woolwich Arsenal in London.

Robert’s Grave

Identifying and burying the dead was an arduous task, completed throughout the war at great expense. The number of deaths was unprecedented in war history. Thousands were buried along the Western Front and not all of them could be easily identified before they were committed to the ground. Expansive World War I graveyards are a visible feature along the Western Front even to this day, with many travelling to see the graves of their relatives.

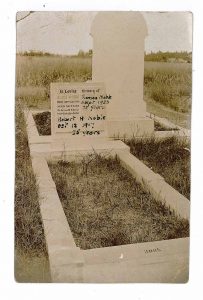

The Australian Infantry Service organised photographs to be taken of graves in Belgium and France, which were then sent on to families in a memorial folder. The example of the left was sent to Robert’s family in 1921.

After a torturous wait, it is fortunate that Robert’s father received the mementos that he did. He died not two years after receiving this memorial folder.

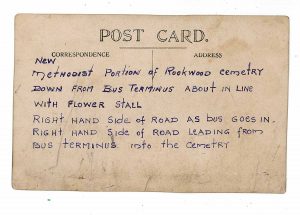

To this day, soldiers classified as ‘missing’ continue to be located and identified in graveyards on the Western Front. For those who did have a record of the final resting place of their loved ones, travel to the site was not feasible. This postcard (see left) shows us one way that family members coped with the distance. Depicted is the grave site of Robert’s father, Thomas, at Rookwood cemetery with Robert’s name inscribed in pen.

This postcard was placed in an envelope dated to the mid 60s when it was given to City of Canterbury Library Service, addressed to Robert’s brother. Clearly forty years on, the young boy who went to war and never returned was still in the minds of his loved ones.

Robert Noble records

- Robert Noble Record – Australian War Memorial

- Robert Noble Record – Canterbury’s Boys

- Robert Noble Record – Remembered with Honour

- Robert Noble Record – Australian Military Forces

- Robert Noble Record – Newspaper clipping

- Robert Noble Record – Valuation

- Robert Noble Record – Sands Directory